Reading List: Shaun Tan

I was driving Phoebe to school on Wednesday morning – she had to be at her desk by 7:30 for a field trip to Ellis Island or else – when I told her that Shaun Tan had sent us a guest post about his formative books for kids. What do you want me to tell people about Shaun’s books, I asked her. What should they know?

His pictures have a lot of feeling, she said.

Okay, I said. But what do they make you feel?

I think about them when I'm daydreaming, she said. Can you stop asking me questions now?

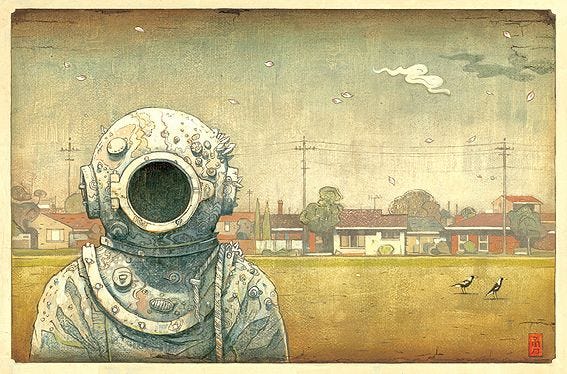

If you got a copy of 121 Books last week -- the little book that Jenny and I gave away here last week -- you might have seen Shaun's book, Tales From Outer Suburbia, sitting there at #91. What you didn't see was what the book actually looks like. I'll start with the cover, which is as evocative and alluring an image as I can recall on the cover of a book. I remember seeing a review of this one in the New York Times Book Review a few years ago and looking at that cover, and thinking: I want to climb inside that book. And once you do, a similarly strange, exquisite, odd, absurd, whimsical, mysterious world awaits. Tales From Outer Suburbia is a collection of stories about, well, about a lot of things, including: a stoic water buffalo who lives in a vacant lot; a tiny stick figure-ish, possibly alien foreign exchange student who sleeps in a teacup and asks to be called, perfectly, Eric; two brothers who argue over whether the earth simply ends at the edge of the map, and then set out on a journey to find out who's right; and a story with the stunningly great title, "Broken Toys," that contains the following two stunningly great sentences: "Well, we'd certainly seen crazy people before -- 'shell-shocked by life' as you once put it. But something pretty strange must have happened to this guy to make him wander about in a spacesuit on a dead-quiet public holiday." How do you not want to read that?

Anyway, if you want to see what Phoebe was talking about re: the emotional punch -- the feeling -- of Shaun's art, check out some of his work. He did a wordless book, The Arrival, whose soulful beauty kind of defies description. He did a picture book, The Lost Thing, which he then turned into a fifteen minute short film, which then won a little known prize called AN ACADEMY FREAKING AWARD. (You can see it here.) The pleasure of having someone this talented on Dinner: A Love Story never gets old -- for us, at least -- and I hope you enjoy Shaun's recommendations. What I love, in particular, is that Shaun -- being an Australian, and an artist -- has so many books below that I'd never heard of, and have now ordered. That, and I also love his use of the word "carnage." Enjoy. -- Andy

I should begin this list with an early "mistake" made by my mother when it came to bedtime reading. She herself did not grow up in a literary household: in fact, as a kid, I was fascinated by the sheer absence of books, or even paper and pencils, in my grandparents’ house -- books just weren't part of their world. Perhaps for this reason, our Mum felt her own children should be exposed to as many books as possible, but at the same time was not guided by (a) experience, or (b) the kinds of lists you find on websites like this. If it looked vaguely interesting, Mum would read it to my brother and me at bedtime. One such title, read to us when I was 7 or 8, was an apparently charming fairytale by some guy named George Orwell: “Mr. Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes…”

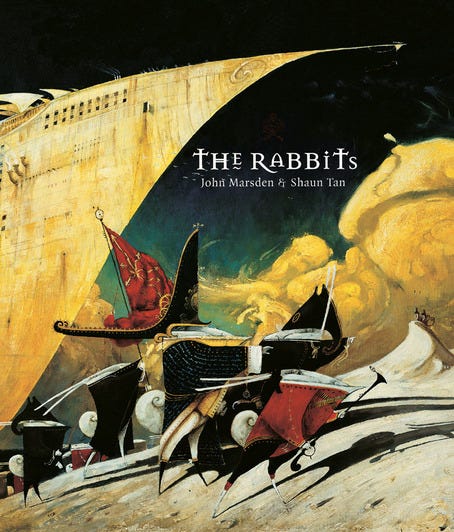

We were all hooked (and, frankly, a bit unsettled) from the outset, so there was no turning back. My brother and I looked forward to each progressively disturbing chapter: conniving pigs, brainwashed sheep, a horse carted off to something called a "knackers" -- poor Mum, having to field all of our questions. I asked her recently about this, and she remembers being increasingly anxious about how the story “might affect your young minds” – yet we voted to keep going (bedtime reading should always be democratic). Of course, the book ends with the pigs celebrating their triumphant depravity, and Mum was very worried about that. As for me, I just thought it was terrific. And it was no more disturbing than stuff I witnessed at school every day, with our occasionally cruel kids and less-than-perfect teachers – I thought Orwell was right on the money. I’d never thought about a story so much after it was read. From then on, I began to appreciate unresolved endings, and to grow tired of the less-convincing, moralizing stuff that kids were being fed in suburban Australia, where I grew up. I realized books weren’t just for entertainment, that they could say something. Animal Farm -- along with Watership Down and Gulliver’s Travels --profoundly influenced my development as an author and illustrator. Most specifically, The Rabbits, an allegory about colonization written by John Marsden and illustrated by me. That was quite a controversial book when it was published -- and was even banned in some Australian schools -- yet very young children seem to enjoy and understand it quite deeply; they grasp, somehow, the hidden optimism that adults often miss. That continues to surprise and delight me, the ability of children to find silver linings in grim stories.

I don’t have children, and don’t specifically write/paint for them. Maybe that’s why kids like my work! I just think of them as smallish people who are smart and creative, and honest in their opinions. So when I think about what makes a great children’s book, I tend to think of books that achieve universality, the widest possible readership – books that appeal to us, from toddlers to geriatrics, in a primal way, and can be understood on many different levels. Picture books are particularly great for this, because they're concise and easily re-read; they often invent their own narrative grammar, as if you are learning how to read all over again.

My interest in picture books only came about later, as an adult artist, as I was moving from painting into commercial illustration and looking for interesting work. The book that really got me interested in picture books -- professionally, I mean, in that "Hmmm, I’d really love to do something like that one day" kind of way --was A Fish in the Sky, written by George Mendoza and illustrated by Milton Glaser. (Even if you don’t know Glaser’s work, you almost certainly do. He's a legendary graphic designer. This book is not easily found, but I urge you to try. I stumbled upon it while doing "research" as a Fine Arts undergrad.) It’s a series of poetic metaphors -- “a fish is not just a fish,” “a walk is the woods is not just being alone" -- illustrated in an indirect, slightly surrealist way. An image of a big yellow flower floating in the middle of a room is particularly resonant for me, as the book is about both the power and fragility of sensory memory – there no particular narrative as such. This approach had a huge impact on me as a "visual writer," and A Fish in the Sky strongly influenced my own picture book about depression, The Red Tree.

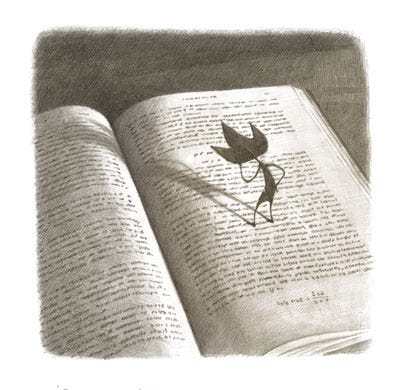

Another book I love along these lines is The Mysteries of Harris Burdick by Chris Van Allsburg. Originally published in 1984, I came across a copy in my outer suburban library in Western Australia, flipped through it, and thought “this is weird – where’s the story?” before putting it back. But my curiosity kept me returning, and the genius of Van Allsburg’s approach to storytelling gradually dawned on me: let the reader do the work! Mysteries is a series of fragments, stories that might have been, each represented by a singular image, a title, and a dislocated sentence. The absence of color only adds to the allure of each quiet enigma: a nun floating on an airborne chair, a lump under the carpet, an ocean liner forcing its way into a tiny canal. In each case, you can’t help but imagine your own story: it’s impossible not to think creatively. Van Allsburg reminds us of what is so special about books – that the reader is a co-creator of the world, not just a recipient; they are the principal director of an author’s screenplay and illustrator’s concept art. That’s a key to being a good writer or illustrator, I think – creative humility. You should never feel smarter than your audience.

While we're on the subject of influence, I’ll list a few other notables that really hooked me when I was an unemployed freelancer, looking for inspiration: Lane Smith’s incredible illustrations for The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Stories, When the Wind Blows by Raymond Briggs, The Starry Messenger by Peter Sis, and Free Lunch by Vivian Walsh and J. Otto Siebold. These books opened my mind to the sophistication and potential – and, yes, craziness – of picture books. They were intriguing, original, funny, and as complex as any real work of art.

It's worth mentioning that Australia has a particularly strong picture book culture, and there's some really amazing work for US readers to check out. Ron Brooks is one of my favorite illustrators, and I’d recommend his book Fox (written by Margaret Wild, a terrific picture book writer not afraid to tackle big subjects). This is a fable with a touch of Orwell about it: a half-blind Dog rescues a crippled Magpie, and together they help each other survive in the bush – until lonely Fox comes along to lure Magpie away. Yet Fox doesn’t want to befriend her or even eat her; he just wants her and Dog to “know what it’s like to be truly alone.” It’s gut-wrenching stuff, and could only ever achieve full impact as a short, seemingly innocent-looking picture book. Children, of course, know all about this kind of social carnage, and no doubt appreciate seeing it represented honestly as much as adults do.

I'd also recommend Armin Greder’s The Island, about a stranger washed ashore on an island of gossipy villagers. They take him in, but become increasingly afraid of his "ominous" presence, even though the man does not say or do anything ominous. This book cuts to the core of all our debates about refugees, particularly here in Australia, a big island with a checkered history when it comes to immigration. Greder’s drawings convey a crucial part of the story through a quiet and expressive style, one I'd call "ugly beauty."

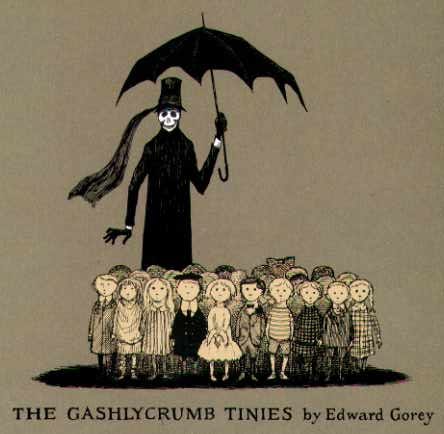

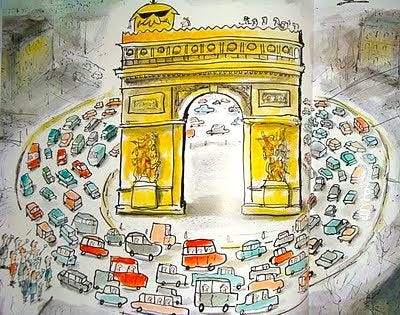

Okay, I realize these are all fairly dark books, which I suppose is a pretty cear reflection of my particular inclinations -- e.g., loving Edward Gorey’s Gashlycrumb Tinies (an alphabet book, containing illustrations of Victorian children meeting their end in novel ways!), and the book I checked out the most than any other at my local library as a kid, The Headless Horseman Rides Tonight by Jack Prelutsky and Arnold Lobel. So to balance things out a bit -- to inject a little light -- I’d recommend Leigh Hobbs’ absurd and hilarious Mr. Chicken Goes to Paris. Hobbs's drawings look very much like dinner-napkin doodles, with all their attendant disregard for continuity or finesse. Our hero, Mr. Chicken, looks a little like a defrosted supermarket chicken with an angry face, fangs and, as described in his passport, "everything yellow." He’s gigantic, a monster with a parson's nose – as an actual nose. He has a friend named Yvonne in Paris, a happy little girl who takes him on a sightseeing tour… and that’s pretty much it! What makes Hobbs’s work so fun, though, is that everything is understated and matter of fact; there’s something quite Australian about this sort of surreal, laconic humour. It’s a quality also present in another of my favorite picture books, The Great Escape from City Zoo, which is about four animals on the run who manage to hold regular jobs and apartments in a city much like New York, where people are likely to overlook the fact that you are actually a flamingo or anteater, so long as you keep your clothes on and pay your taxes. Just don’t fall on your back if you’re a turtle, or faint outside a taxidermist’s shop window!

Lately, my own work has been drifting into that wonderful gray area between picture books and comic books, so I’ve been reading a lot of graphic novels, which are also, in turn, informing my work as a film-maker. I say "gray" partly because of blurry definition boundaries – panels, pages, word bubbles – but also because the audience for graphic novels can be hard to pin down, though these books are often more "young adult" than "children’s." But again, the best ones are those that cross over and appeal widely, and here I would include, once again, the work of Raymond Briggs, particularly The Snowman (which greatly influenced by own book, The Arrival) and the biography of his parents, Ethel and Ernest. Then there's American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang, which was personally very resonant for me: as an Australian-born half-Chinese growing up in a very non-Asian place, I recognize a lot of Yang’s neuroses (also dealt with in the work of Adrian Tomine, who’s very faulty protagonists look, eerily, just like me!). Skim by Canadian cousins Jillian and Mariko Tamaki deals with some similar themes from a female perspective, plus a whole lot of other teenage angst, perfectly pitched. A big theme of many graphic novels, of course, is marginality – where the medium and message have a bit in common. Stitches by David Small, Blankets by Craig Thompson, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi: they're all about individuals looking for meaning in a confusing, troubled world – which could be said about my own work, too.

I'm sure we'll be seeing interesting things very soon in the world of e-books, but I do believe that the traditional picture book – words and images printed on pieces of paper – is hard to beat. Books are actually objects, and that’s a big part of their appeal. Their physical limitations inspire creative problem solving -- I find that my best work grows out of formal restrictions. I’ve dabbled with a lot of other things, but always seem to come back to picture books as the perfect vehicle for creating simple, complex little worlds that everyone can enjoy, and revisit at different times in their life.