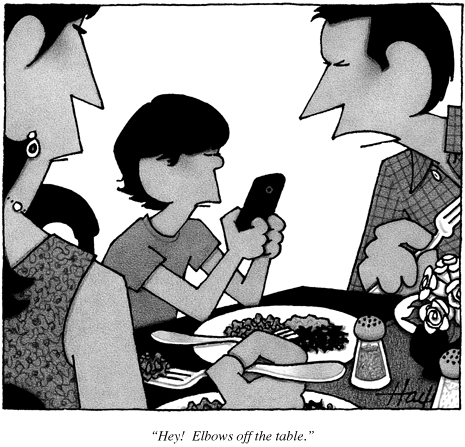

The Lost Art of Conversation

Sherry Turkle, an MIT professor who has been researching the effect of technology on relationships and behavior for thirty years, first got my attention a few years ago when her book Alone Together was published. If our kids are always tethered to their devices, she said in one interview (I'm paraphrasing), if they don't know how to be alone with themse…